Entertainment

Texas Shaken Baby Cases Highlight the Death Penalty’s Flaws

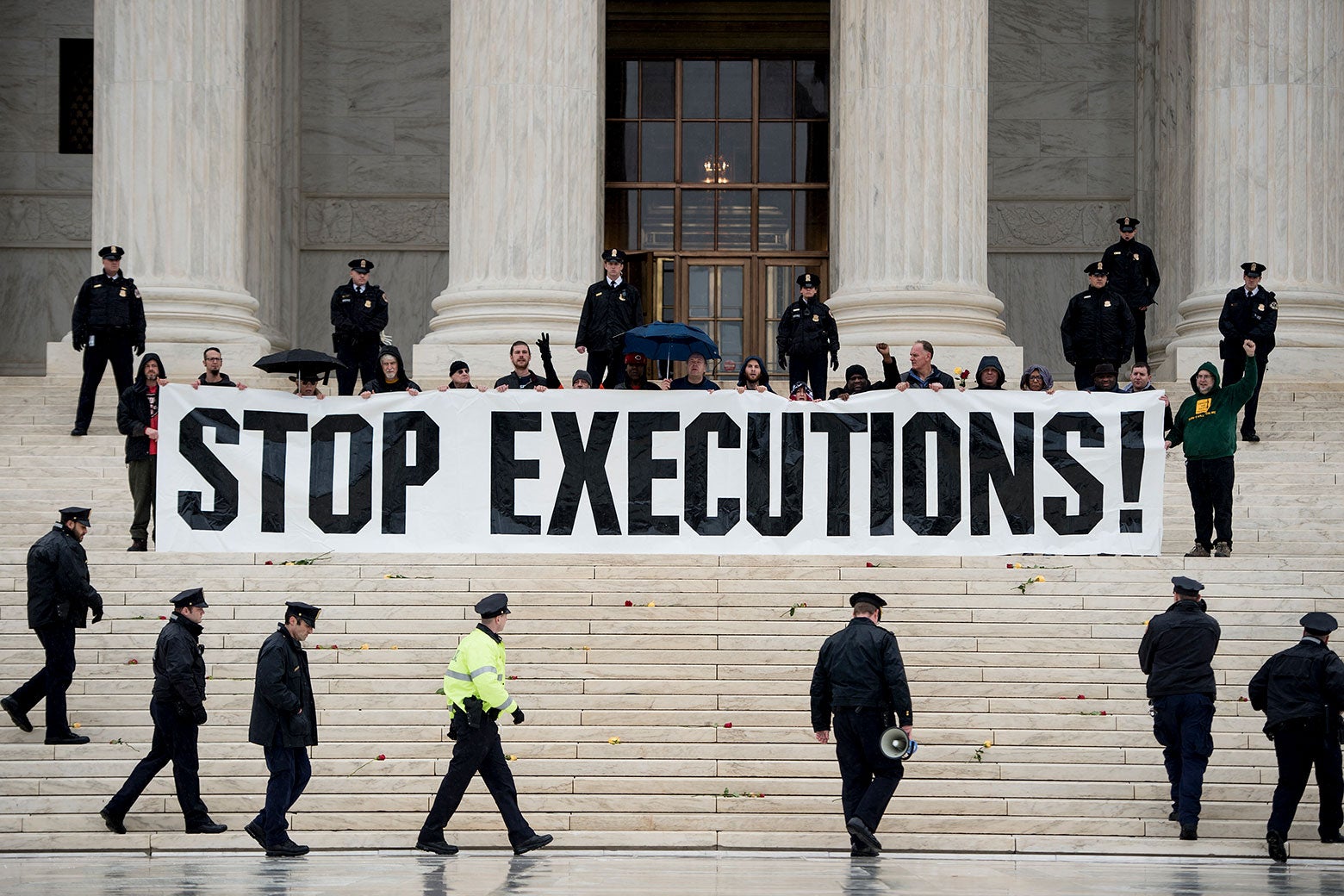

Two recent cases from Texas involving the so-called “shaken baby syndrome” have reignited the debate about the death penalty in America, exposing serious flaws in the justice system. Both incidents involved parents convicted of murdering their 2-year-old children, highlighting a disturbing pattern of wrongful convictions that often seem impervious to evidence of innocence.

In one of these shocking cases, a trial judge has declared Melissa Lucio, one of the few women on death row in the U.S., to be “actually innocent.” Lucio was found guilty in 2008 for the murder of her daughter, but significant doubts have now surfaced about the validity of that conviction. Unfortunately, her battle is far from over, as the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals—known for its strong pro-death penalty stance—must confirm this ruling.

Simultaneously, the Texas Supreme Court has greenlit the execution of Robert Roberson, convicted in 2002 for allegedly killing his 2-year-old daughter. This case relied heavily on evidence related to shaken baby syndrome, a theory that has since been discredited in several states including Texas. It’s now widely believed that Roberson’s daughter’s death was likely accidental rather than a criminal act.

Americans may find it hard to believe that evidence proving innocence could fail to secure freedom for someone on death row. Yet the reality, particularly in Texas, is grim. Victims of wrongful convictions often face insurmountable barriers to exoneration. Even when compelling evidence arises, it does not always equate to definitive proof of innocence, leading to persistent uncertainty.

Law professor Lee Loevinger pointed out decades ago that judges and juries are rarely in touch with the “facts” of a case, relying on testimonies and limited documentation. This detachment complicates the pursuit of justice.

Prosecutors, much like individuals, are often unwilling to concede mistakes, especially in high-stakes situations. New York Times writer Emily Bazelon has described these prosecutors as “innocence deniers,” noting their tendency to hold onto flawed convictions, even in light of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Moreover, procedural hurdles complicate matters. Evidence proving innocence may become available long after the time frame for filing claims has expired, forcing courts and prosecutors to prioritize finality over justice. In 2022, the Supreme Court underscored this with a ruling that questioned the value of review once a state court has rendered a decision.

In the Roberson case, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals aligned with this perspective, neglecting to weigh evidence of innocence. Instead, it focused on a narrow legal issue regarding a legislative inquiry, asserting that there was no judicial basis to delay an imminent execution. This decision illustrates a troubling preference for procedural finality over a genuine quest for justice.

Conversely, in Melissa Lucio’s case, the evidence of miscarriage is stark. The district attorney and Lucio’s legal representatives agreed that key evidence had been suppressed during the original trial. A judge has now identified that the state withheld vital evidence, which could have significantly clouded the original conviction.

The question remains whether the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals will uphold the judge’s ruling on Lucio’s innocence or choose to prioritize other factors that might allow the execution to proceed. For states like Texas that choose to enforce the death penalty, the onus is on them to ensure that they do not execute innocent individuals—a seemingly insurmountable challenge in our current system. The tragic reality is that this issue is paramount in death penalty discussions, yet we struggle to address it effectively.